Insights|

Interactive entertainment is cannabilising media

Every generation since the 1970s has its own experience with video games. The earliest, two-dimensional games, like Pong and Pac-Man, have morphed over the decades into something much more substantial than anyone could have imagined. It is not just the graphics and consoles that have evolved: in moving online, games and gamification have become intrinsic parts of our daily lives, blurred into our entertainment and part of our banking apps.

null

Young people choose games as their primary form of entertainment because this entertainment is immersive. You cannot jump into the world of a film or a television show, but you can within a game. Gen Z chooses to play in virtual worlds over Netflix or Amazon Prime and does not regard it as a special, separate behaviour. Unlike the generations above them, everything Gen Z does is now Internet-native, whether it's work, school or play.

We believe that this cannibalisation of media is a long-term trend, and that we will see film and TV continue to be swallowed up by video games to the extent that, in 20 or 30 years’ time, we may never watch ‘static’ film and TV. Everything will have an interactive component. This means that what we consider to be entertainment will shift towards being something where interactivity is the default behaviour.

The most important development, in our opinion, is that players’ perception of value has shifted. For my generation (Millennial), there is still a clear differentiation between value online and value offline: I do not value a digital coffee as highly as I value a real-world coffee. For Gen Z and below, that line is distinctly blurred: digital goods and digital pastimes carry almost equal value in comparison to offline purchases and events, and that trend is accelerating. Some of the most popular games that have come out recently, such as Roblox, Among Us or Fortnite, are the first example of this value shift.

"The mix of very large-scale trends therefore creates a distinct probability that a massive social network could erupt out of the video game space"

The question of players’ identities – and how players project themselves into a world – is also becoming significantly more prominent. Currently, there is no common ‘you’ that jumps between these worlds (games) – there is a different character for each experience that the developer or publisher owns, and players must invest meaningful time (up to an hour) at the start of these games in recreating their identity, over and over again. Epic Games, the creator of Fortnite, is vocal in advocating for a ‘metaverse’, a ‘world of video game worlds’ analogous to the fictional ‘Oasis’ from the 2011 Ernest Cline novel, Ready Player One. It is our opinion that a Metaverse of some sort will inevitably exist, though the time horizon within which this will happen is debatable: the technical infrastructure such a rich, 3-D environment would require to sustainably operate 24/7/365 implies to us that this will not emerge for at least 10 years, but that such an environment will allow you to jump between worlds as yourself, be recognisable to your friends and family, and perform activities such as shopping or even physical exercise – things that we might not associate with video games, today.

This mix of very large-scale trends therefore creates a distinct probability that a massive social network could erupt out of the video game space. The next generation of teenagers, instead of going to Facebook or Instagram, could be opening up a video game in their hundreds of millions and spending their time hanging out with their friends there. These demographic trends and shifts give renewed importance to the Interactive Entertainment sector more broadly, and that is why we pay attention to the key changes and characteristics happening now and over the next few years.

What does the market look like?

Indeed, one might assume that video games content is driven by America or Japan, which gave us Sonic and Mario, respectively. In fact, Europe has been the creative and cultural hub of much world-leading IP. Candy Crush, Max Payne, Hitman and new hit Valheim (which sold 4 million units in 3 weeks and climbing), as well as the most popular massively-multiplayer online (MMO) or racing games all come from Europe. There are at least 10 large-scale (EUR1 billion+) games companies in Europe that have a significant impact upon the industry, including Ubisoft in France and CD Projekt Red in Poland (which released the hugely-anticipated Cyberpunk 2077 over Christmas).

With consolidation, these European companies are getting bigger. A huge wave of mergers and acquisitions in the industry over the last five years is continuing to accelerate and a lot of the deal flow is in Europe. Simultaneously, there is growing American investor interest in the sector as well.

There’s no such thing as a typical gamer

The profile of the ‘gamer’ is changing. The historical stereotype of the 16–24 year old male is evaporating quickly. Development studios are now producing games for broader demographics and more diverse audiences. Lakestar has made two investments that capture this specific trend. One of these investments, Netspeak Games, founded by Callum Brighting, is making a safe, virtual and mobile world primarily aimed at diverse audiences who enjoy games, and focussed fostering friendly, social connections.

What makes a video games company successful?

The founder and team itself is absolutely at the top of the pyramid in importance. Put succinctly, the experience of a great games developer, who has been through some of the top studios in the world and decides to go independent to produce their own title, is not something that you can easily replicate anywhere else. Skill in this industry is not commodified, nor is leadership or creativity. We are incredibly proud of the six entrepreneurs we have backed to-date, all of whom have exemplary backgrounds in industry and gave us tremendous confidence in our decision to invest.

Secondly, the sector is no longer the ‘hits-driven’ industry it has been perceived to be. In fact, while there are indeed big hits, such as Fortnite, they are becoming more frequent and lasting a lot longer, too — to the tune of 10 to 15 years of meaningful revenue and cash flow (Counter-Strike, League of Legends, World of Warcraft or Clash of Clans are some good examples, here). It is now viable to make a game that is not a hit but that still produces hundreds of millions of dollars in profit every year and achieves a venture-scale outcome. While it may not attract the same level of industry press, for an investor these outcomes can still drive meaningful fund performance, particularly given the speed with which this can happen in video games. Historical examples of this would include Small Giant Games and NaturalMotion (both sold to Zynga), as well as Codemasters (IPO and subsequently acquired by EA) and Jagex (most recently acquired by Carlyle Group).

Lastly, if a developer gets it right, they immediately begin generating not just revenue but high margin cash flow. This dynamic is what makes games companies so different from other sectors: with games, you have six to eight months to find product-market fit and if, when you push the game out, it is not there, then you drop the game and start again. But how do you ‘find’ success?

A numbers game

The video games industry has transformed over the past decade to become a very data-driven industry that has more in common with SaaS businesses, in metric terms, than anything else. The parallels in KPIs monitored as indicators of scalability are clear: we track information such as average session time, daily sessions and daily, weekly or monthly active users, long-term cohort-based retention… all of these data points are rigorously monitored and optimised for, just as in SaaS.

When we make an investment in a team, we can start to get very early data within about three to six months on how their games are performing with small audiences, and that is indicative of the potential success of that title.

The 10-year view: shopping and concerts, too

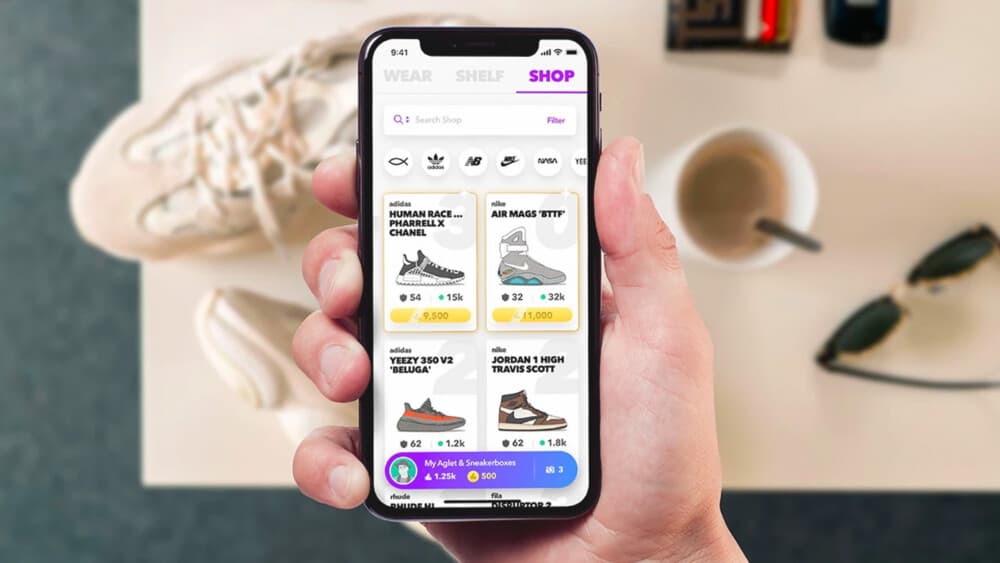

We are starting to see crossover with ‘real life’ in gaming. To-date, most of this behaviour has been in the form of one-off marketing stunts, such as hosting ‘virtual concerts’ with real celebrities (Travis Scott and Massive Attack, to name a couple). In these events, a band or artist will come and perform in these virtual worlds and you, as a character, can run around with them on-stage and experience the ‘show’ in a way that you could not possibly do so in real life. Similarly, we can apply this crossover to next-generation e-commerce. Brands will need to think about their digital presence in virtual worlds, and we invested in Aglet for this reason. If brands have a virtual store in something like Fortnite, they need to figure out how to handle fulfilment if someone buys goods in that store.

"The point is that the retail experience can be decoupled from the physical environment to create truly novel commercial experiences"

Lastly, there are a number of companies now focussing on at-home fitness and workout routines in virtual reality environments. We are monitoring this sector closely, as it combines the broader societal trends of Fitness and Health awareness with gaming and at-home exercise, as popularised by Peloton.

If anyone has a chance at taking this mainstream, it is Apple. A spatially-aware pair of AR glasses could mean, for example, that you could be walking down the street, pass your local bank and glance in the window to see your account details and balance displayed there, although only you would be able to see this information, via your glasses.

Just next door could be a clothes shop, where the clothes displayed in the window are posed on your own avatar, in your size. This sounds like sci-fi fantasy, but it is not unrealistic to think this will be commercially available in less than a decade: such a world requires immense graphics processing power at data centre scale, which is why we believe it is no coincidence that Amazon and Google have launched ‘Cloud Game Streaming’ services in the past two years: it creates a commercial rationale (‘Netflix, but for video games’) that has broad appeal and justifies tens of billions of dollars of investment into graphics infrastructure that can enable this future.

This article is part of the Lakestar Briefing, a periodical publication about Lakestar's portfolio companies and our network of inspiring minds we like to work with.

Click here to subscribe